Extension members in C# 14

Extension members are the largest new feature of C# 14. We have been hearing about it for quite a while, also under the name of extension everything and extension types. It was expected to be released in C# 13, but then postponed. Now it's finally here. With a different syntax and some functionalities removed (explicit extensions, for example). But it's still a big addition to the language.

Extension methods have been a part of the language since C# 3 when they were introduced together with LINQ:

public static class StringExtensions

{

public static string? FirstCharToUpper(this string? receiver)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(receiver))

{

return receiver;

}

else

{

return string.Concat(receiver[0..1].ToUpper(), receiver.AsSpan(1));

}

}

}

Since they could be invoked using the same syntax as instance methods, they seemingly allowed adding methods to classes without having access to their source code and recompiling them:

"foo".FirstCharToUpper().ShouldBe("Foo");

Extension members in C# 14 introduce a new syntax to define such extension methods:

public static class StringExtensions

{

extension(string? receiver)

{

public string? FirstCharToUpper()

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(receiver))

{

return receiver;

}

else

{

return string.Concat(receiver[0..1].ToUpper(), receiver.AsSpan(1));

}

}

}

}

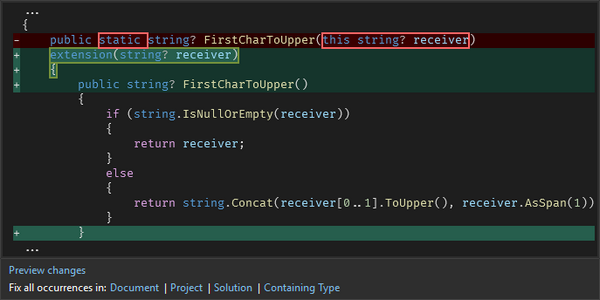

With this new syntax, you move the so-called receiver (i.e., the parameter referencing the class you are extending) from the method signature to the containing extension block. There's even a recommendation in Visual Studio which does this for you and nicely shows the differences between the old and the new syntax:

Of course, you don't need to convert your existing extension methods to the new syntax. However, the new syntax allows you to define other types of extension members in addition to instance methods:

Instance properties couldn't be defined with the old syntax, because properties don't have parameters to add the receiver to. There's no need for that with the new syntax because you specify the receiver in the

extensionblock. Keep in mind, though, that you're not modifying the receiver class so you can't add fields to it. This means that you can't define automatically implemented extension properties or use the new field keyword in extension property setters and getters:public static class StringExtensions { extension(string? receiver) { public bool IsEmptyField { get => string.IsNullOrEmpty(receiver) || receiver == "N/A"; } } }Static methods couldn't be defined with the old syntax because there is no instance of the class you are extending to add as a parameter. With the new syntax, you are not allowed to reference the receiver instance from the

extensionblock. You can even omit its name if you define only static members inside it:public static class StringExtensions { extension(string?) { public static string? Create(string? pattern, int count) { if (pattern == null) { return null; } if (pattern.Length == 0 || count <= 0) { return string.Empty; } var builder = new StringBuilder(pattern.Length * count); for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) { builder.Append(pattern); } return builder.ToString(); } } }Operators couldn't be defined for the same reason as static methods: there is no instance of the class you are extending, although at least one of the operator parameters will (have to) match the type of the receiver class (similar to how at least one parameter of a non-extension operator must match the type of the containing class):

public static class StringExtensions { extension(string?) { public static string? operator *(string? pattern, int count) { return string.Create(pattern, count); } } }Static properties couldn't be defined with the old syntax for both reasons previously mentioned: they don't have parameters and there's no instance of the receiver class. With the new syntax, that's not a problem:

public static class DoubleExtensions { extension(double) { public static double One => 1.0; } }

All of these members can be accessed like you would expect them to, i.e., as if they were actual members of the receiver class:

"foo".IsEmptyField.ShouldBe(false);

string.Create("foo", 3).ShouldBe("foofoofoo");

double.One.ShouldBe(1);

You can declare as many members in a single extension block as you want, both instance and static. And you can have as many extension blocks inside a single static class as you want, even for different receiver types.

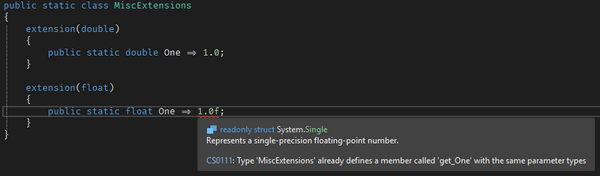

However, you can't declare members with the same signature inside a single static class, even if they are placed in extension blocks with different receiver types and would therefore extend different classes:

If you put the members in two different static classes, the compiler won't complain anymore:

public static class DoubleExtensions

{

extension(double)

{

public static double One => 1.0;

}

}

public static class FloatExtension

{

extension(float)

{

public static float One => 1.0f;

}

}

You can even declare extension methods for static classes. Of course, you're limited to static extension members since static classes can't have instance members:

public static class PathExtensions

{

extension(Path)

{

public static FileSystemEntryType? GetEntryType(string path)

{

if (Directory.Exists(path))

{

return FileSystemEntryType.Directory;

}

if (File.Exists(path))

{

return FileSystemEntryType.File;

}

return null;

}

}

}

Just like null-conditional assignment and field keyword, most extension members work even in .NET 9. Only extension operators require .NET 10 preview 7 or later. You also have to set the language version for your project to preview:

<PropertyGroup>

<LangVersion>preview</LangVersion>

</PropertyGroup>

You can try the feature yourself if you have the latest version (17.14.12) of Visual Studio 2022 installed. It will show you some bogus errors and warnings in the editor, but they don't prevent you from writing and running the code. I'm sure these issues will be fixed before the official release of C# 14 and .NET 10.

You can find a sample project with all the extension members from this post in my GitHub repository. You can look at the accompanying tests to see how they can be invoked.

The extension member syntax will take some getting used to. I do think it's worth the effort to learn, though. Although you could write any extension member as a helper method, the consuming code can be much easier to read if you use them as extension members instead.